“…all of them (bison) are the same, they’re everywhere, you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all” – Roadside Tourist in Yellowstone.

In contrast to the quote above, nothing could be further from the truth when in the presence of the diversity and beauty of nature. It is seldom that we truly appreciate the power of the individual to move and shape us. You only have to start drawing or modeling a bison to realize that one cow bison cannot substitute for another – they are not carbon copy animals milling about in a neat, uniformly responsive herds. They have different hairdos, wildly divergent horn features, body types, behaviors, etc, and why not? These wild animals, of all species, are as uniquely individual as we are.

Sketching “Godzilla,” from a safe perch atop my vehicle. Photo by Brad Orsted.

Individual personality in people is a ‘given,’ but in my world, this clearly applies to wild animals as well. Some may only be known for a few hours, maybe a day, while others have shared their entire lives with those humans willing enough to be patient and observe. Here in Yellowstone this means animals like grizzly bears 264, 211 (aka “Scarface”), “Quad Mom,” and black bear “Roosy”, Bull elk #10, #6, or “Roman”, wolves 21M, 42F, 830 (aka, the “’06 Female”), 113M, 302M, #7F, the sandhill crane “Bent Toe,” and so many other unmarked bison, bighorn sheep, osprey, pronghorn, peregrine falcons, coyotes, bald eagles, etcetera. This is one of the great gifts that Yellowstone offers – a chance to connect with individuals from another

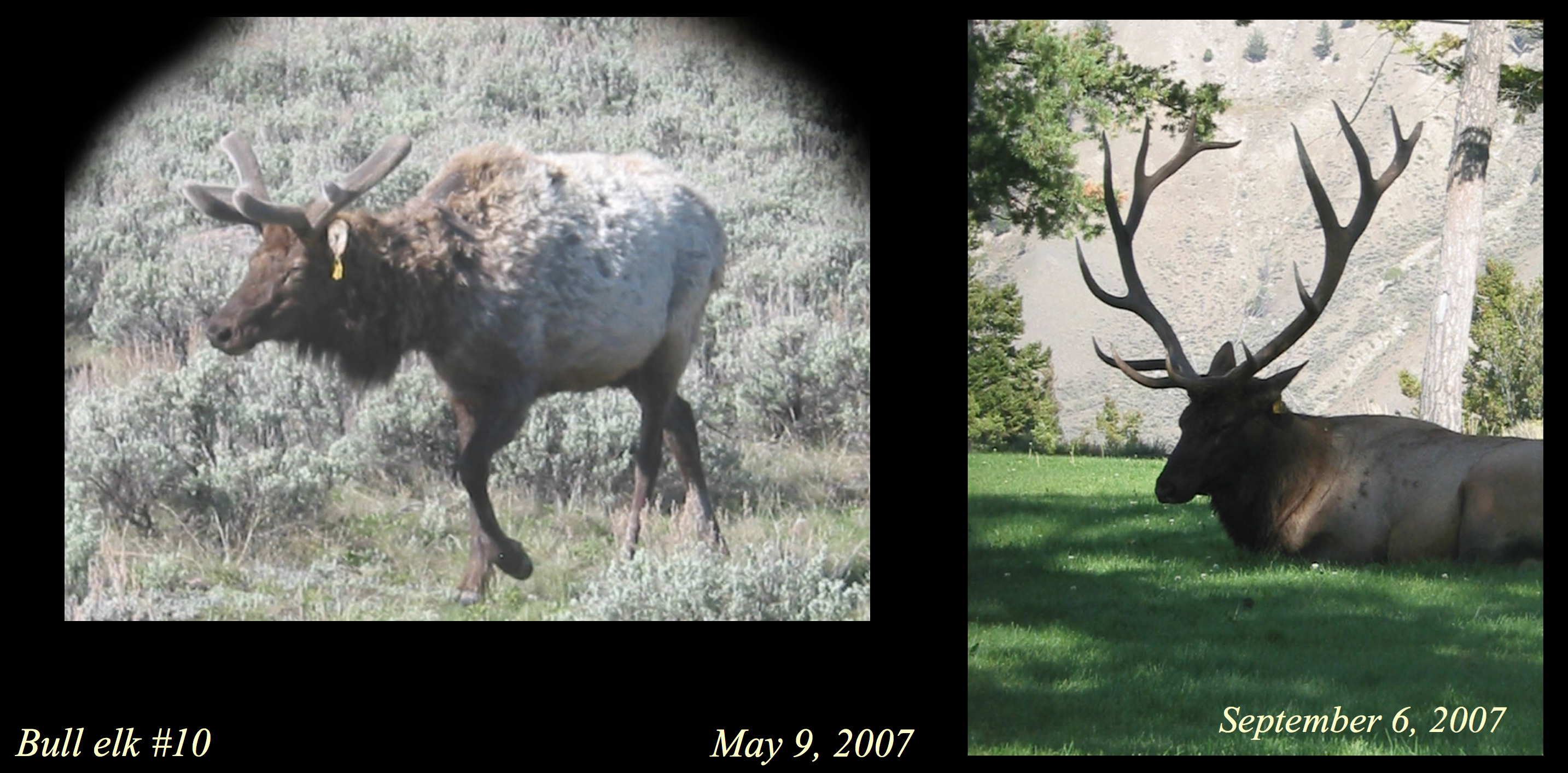

A good, old friend – Bull #10. We knew him for many years and got to watch him across great swaths of the year from growing his antlers (left) in May to reclining in all his majesty in early September.

species. They teach us about the world as seen through their eyes, smelled through their nostrils, heard through their ears and along the way, display their own brand of style, joy, displeasure, compassion, attitude, loyalty, fortitude, charm, bravery… and in turn, come to give us insights about our own lives. I think Henry Beston stated it well when he wrote:

“Scarface” was a famous grizzly bear that roamed the Yellowstone Ecosystem far and wide for 25 years. Some believed him to have teleportation powers as he seemed be able to be in one corner of the Park one day and then in a completely different one the next. He regularly criss-crossed the roads and lent himself to many a photograph. Like other ‘regulars’ and residents, I knew “Scarface” well and hardly needed to see his facial scar or ‘lop-ear’ to recognize this old friend. These small models done of him are tributes to his “Veteran Traveler” status (left) and his seeming thoughtful and complicit mingling with the public in “Lamar Contemplation” (right).

“We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.”

Clockwise from top-left: “The White Lady” alpha female of the Yellowstone Canyon Pack, a resident bull bison, “Like A Rock” that I had the pleasure to knowing one spring, “Brutus,” the star of Montana Grizzly Encounter’s education center near Bozeman, Montana, the “’06 Female” aka 832F alpha female of the Lamar Canyon Wolf Pack, “The Matriarch” bison who led a small band of younger bison near our house one winter, “Something in the Air,” of a well known female grizzly from the Fishing Bridge area of Yellowstone and “Yoga Bear” observed one late autumn following wolf packs and taking their kills through Christmas time and almost into New Years before denning.

As a scientist, I was trained tot study animals without anthropomorphizing (attributing human characteristics to animals). As an artist however, I find that anthropomorphizing is a powerful, if not essential tool for understanding the possibilities in wild creatures and ourselves. To me, studying these old friends helps to go beyond the field guide, or surface-level view, as a way to see the world from a particular animal’s unique perspective. The more I study these animals the more I realize there is to learn…

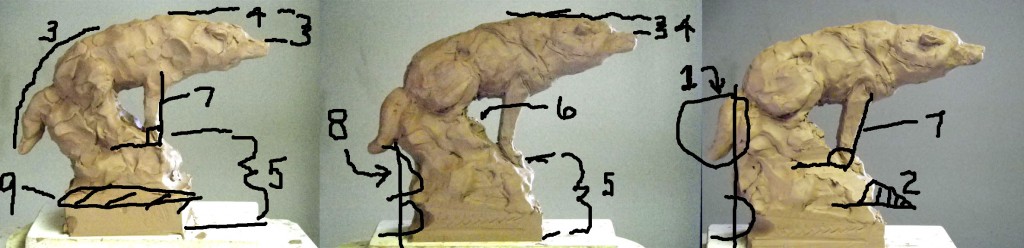

A few more hours are in on the big grizzly bust…

A few more hours are in on the big grizzly bust…

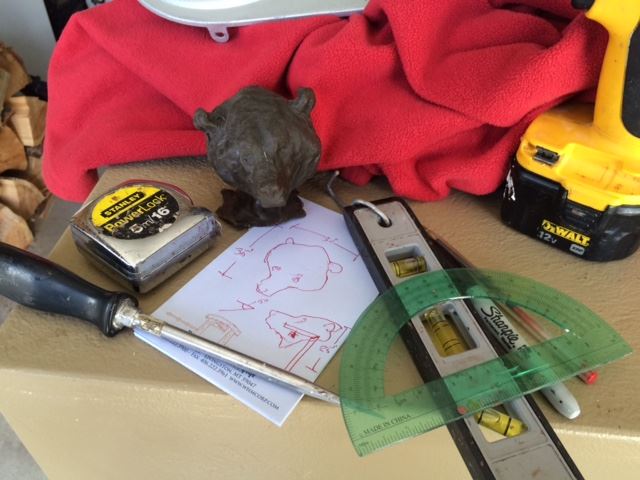

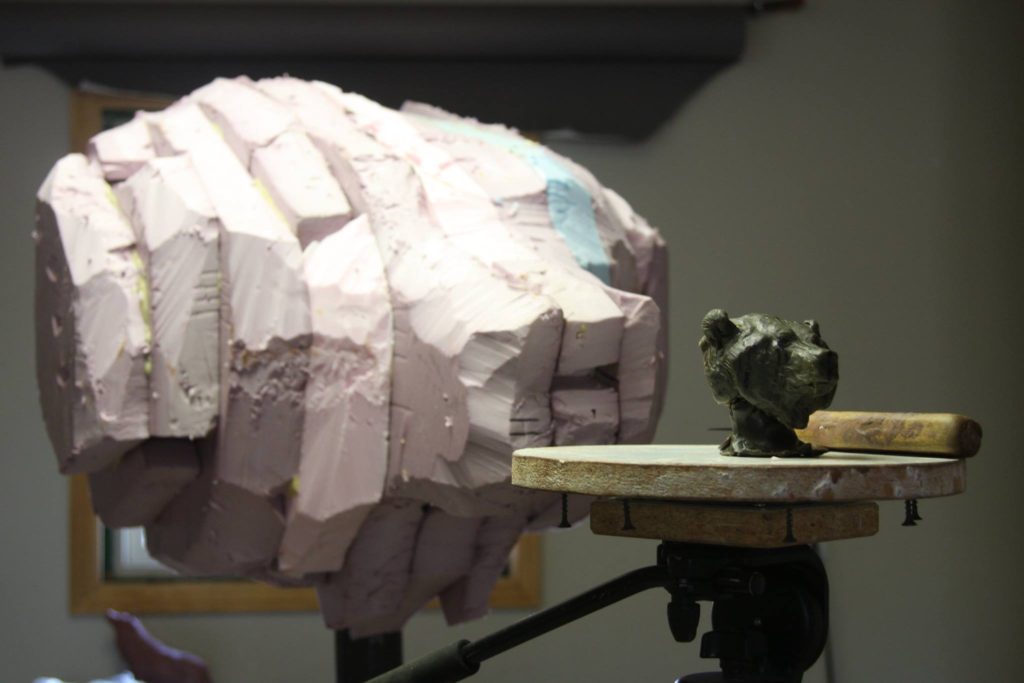

Planning out the layout and design of the larger bear bust….

Planning out the layout and design of the larger bear bust….

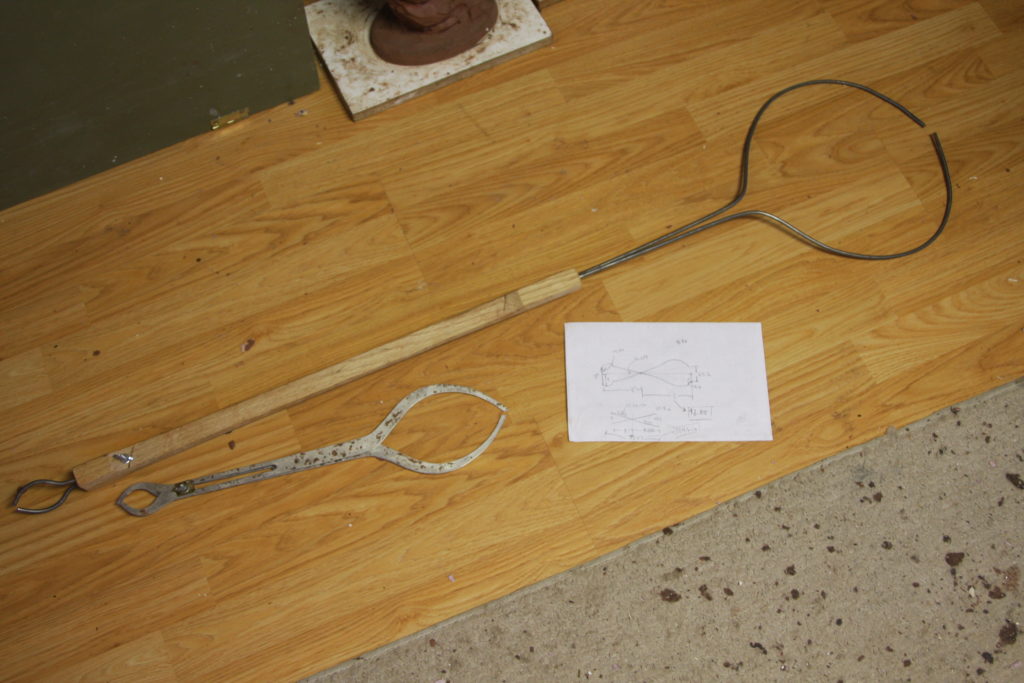

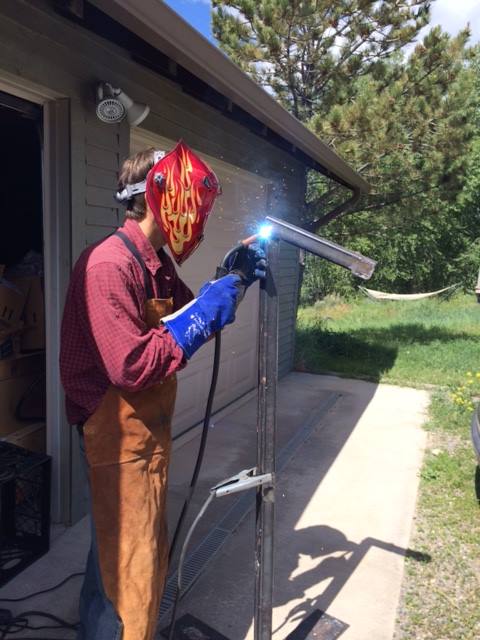

Welding up the steel support post for the larger sculpture.

Welding up the steel support post for the larger sculpture.

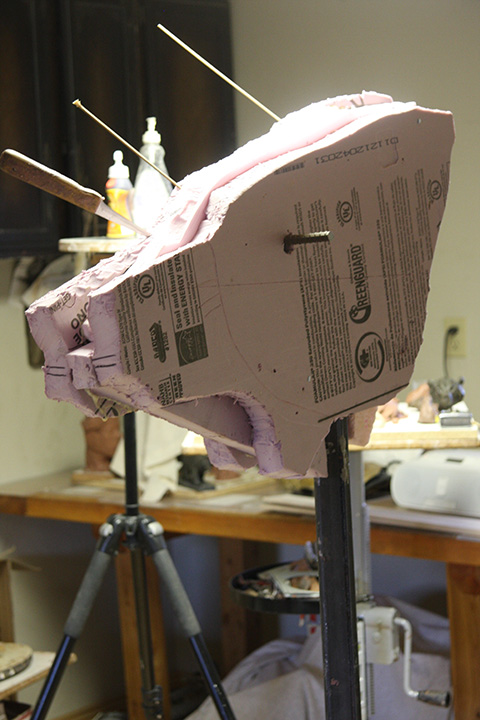

Glueing the styrofoam sheets together under a little extra weight and placing the first pieces onto the steel support.

Glueing the styrofoam sheets together under a little extra weight and placing the first pieces onto the steel support.

tries to capture the immensity of a grand experience in something as limited as paint, pencil, clay or musical notes on a scale. The main goal is to endure the struggle with your medium long enough for it to speak to the poetry spinning inside you & from the subject. My cougar sculpture has re-entered the ugly stage… One hopes that by degrees, the ugly episodes yield to some higher state of beauty & grace. After struggling with this design for many months, I just had the chance to intensely study four mountain lions from life. Three, 7-hour days were spent just watching. I did make a few drawings and started two small sculptures on site but later discarded the latter. Sometimes our desire to ‘do’ gets in the way of our ability to see all of what lies before us…

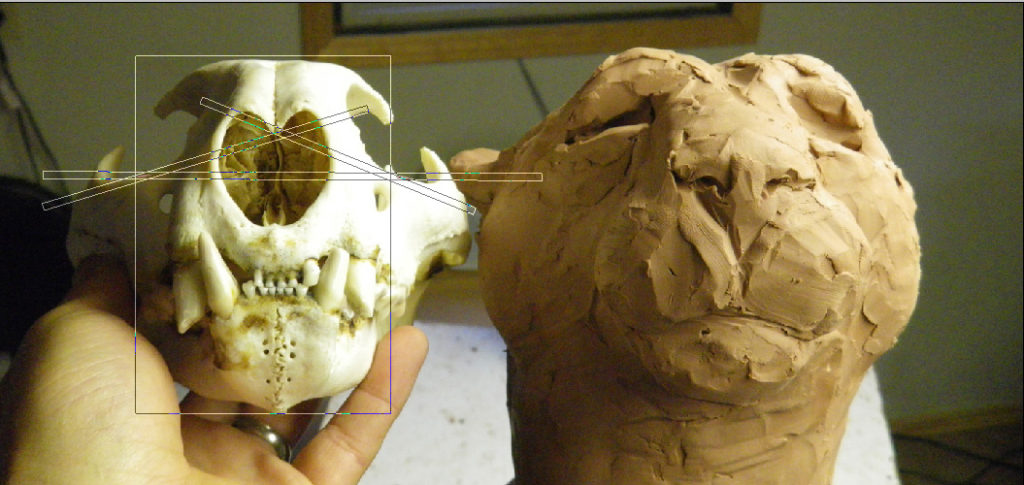

tries to capture the immensity of a grand experience in something as limited as paint, pencil, clay or musical notes on a scale. The main goal is to endure the struggle with your medium long enough for it to speak to the poetry spinning inside you & from the subject. My cougar sculpture has re-entered the ugly stage… One hopes that by degrees, the ugly episodes yield to some higher state of beauty & grace. After struggling with this design for many months, I just had the chance to intensely study four mountain lions from life. Three, 7-hour days were spent just watching. I did make a few drawings and started two small sculptures on site but later discarded the latter. Sometimes our desire to ‘do’ gets in the way of our ability to see all of what lies before us… Here (above) I am comparing the skeletal features of the eye orbits with the sculpture at the right to make sure that a skull exists in that hunk of clay. I added the lines over the photo to give the reader a sense of where my mind travels on these exploratory missions of the subject. Eyes, ears and noses all must fall in their proper place and the skeleton is the roadmap for these and all features of the cat. Below is the a recent incarnation of the sculpture of the mountain lion. It has changed since this photo was taken and will continue to do so until the idea, the forms, anatomy and all the other factors begin to more tightly orbit my notion of what this work means.

Here (above) I am comparing the skeletal features of the eye orbits with the sculpture at the right to make sure that a skull exists in that hunk of clay. I added the lines over the photo to give the reader a sense of where my mind travels on these exploratory missions of the subject. Eyes, ears and noses all must fall in their proper place and the skeleton is the roadmap for these and all features of the cat. Below is the a recent incarnation of the sculpture of the mountain lion. It has changed since this photo was taken and will continue to do so until the idea, the forms, anatomy and all the other factors begin to more tightly orbit my notion of what this work means.

in my mind immediately jumped to some of the research on Yellowstone wolves showing how the body gestures of wolves convey the seriousness of their hunting efforts to their prey. When wolves have zeroed in on a particular animal, their gait increases, their head is lowered and tail straightened out to the back, rather than up as their heads and tails are when searching out a prospective meal. With this in mind, I looked back at our female Labrador, Casey, who had a ‘hunting’ body posture as she was darting amongst the prickly pear cactus. I wondered if this was signaling to those deer what the wolves do during a chase? From there, my mind jumped to the fact that wolves and coyotes must get spines in their feet during some of these chases. This gave me the overwhelming feeling of empathy for them in that powerlessness state of not being able to tend to their own injuries, or not having people to care for them as our dogs do. We all know this feeling to a degree when we become injured or encounter things, people, situations in life that we cannot change.

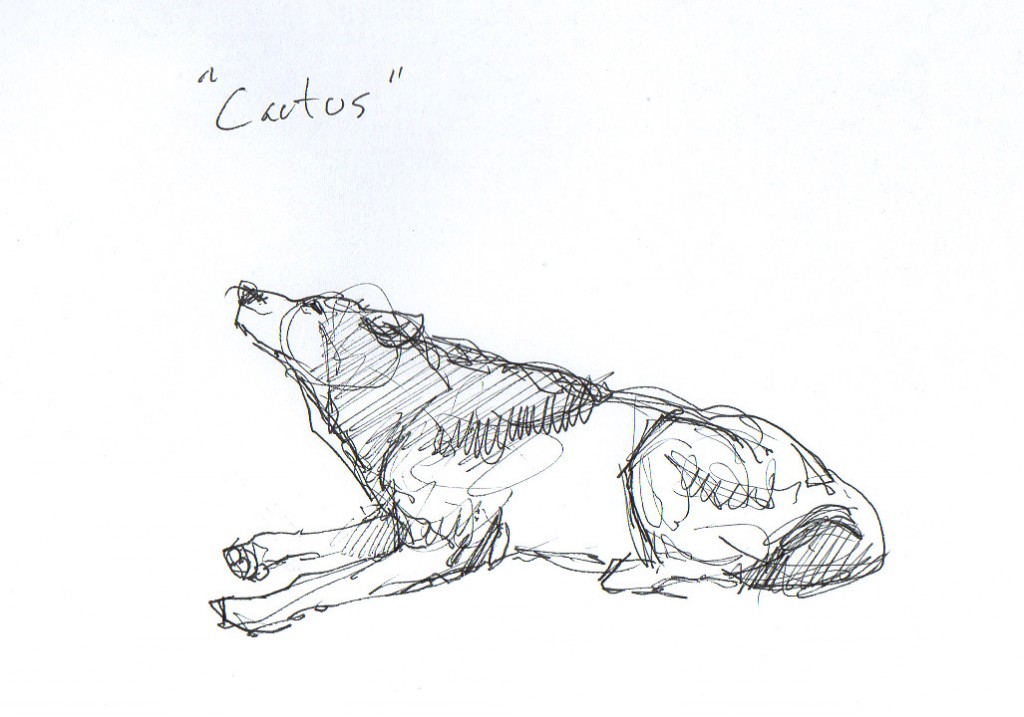

in my mind immediately jumped to some of the research on Yellowstone wolves showing how the body gestures of wolves convey the seriousness of their hunting efforts to their prey. When wolves have zeroed in on a particular animal, their gait increases, their head is lowered and tail straightened out to the back, rather than up as their heads and tails are when searching out a prospective meal. With this in mind, I looked back at our female Labrador, Casey, who had a ‘hunting’ body posture as she was darting amongst the prickly pear cactus. I wondered if this was signaling to those deer what the wolves do during a chase? From there, my mind jumped to the fact that wolves and coyotes must get spines in their feet during some of these chases. This gave me the overwhelming feeling of empathy for them in that powerlessness state of not being able to tend to their own injuries, or not having people to care for them as our dogs do. We all know this feeling to a degree when we become injured or encounter things, people, situations in life that we cannot change.  To fight them does no good, to complain often does even less – SO, I began thinking of a piece that spoke to that notion. Once I got home I made a quick sketch on paper (above) out of my head of the position our male Labrador takes when worrying his feet from cactus spines. I wanted to use those gestures as exemplified by a coyote as the subject to convey this idea. I later made this small wax study to test the idea in 3D (to the right & below). I soon felt that it needed something ‘more’ and the cactus (scaled to south Texas size as our cactus are quite small in Montana) seemed to balance the design nicely – as well as to lend context to the animal’s slightly unusual position.

To fight them does no good, to complain often does even less – SO, I began thinking of a piece that spoke to that notion. Once I got home I made a quick sketch on paper (above) out of my head of the position our male Labrador takes when worrying his feet from cactus spines. I wanted to use those gestures as exemplified by a coyote as the subject to convey this idea. I later made this small wax study to test the idea in 3D (to the right & below). I soon felt that it needed something ‘more’ and the cactus (scaled to south Texas size as our cactus are quite small in Montana) seemed to balance the design nicely – as well as to lend context to the animal’s slightly unusual position.